A spotlight exhibition focusing on ceramics produced in the workshops of Kashan between c. 1150-1280, this group of five lustre-painted bowls illustrates the technical and aesthetic heights achieved by the Kashan potters through the innovative combination of a siliceous stone-paste ceramic body with lustre-painted surfaces. The perfection of these technologies led in turn to the development of an exclusive ornamental language distinctive to the Kashan workshops, which raised the status and appeal of the ceramics made there to a level unprecedented and never again supplanted in the history of ceramics production in the Islamic world. This exhibition celebrates the exquisite craftsmanship that went into the making of these bowls, and explores the development of the Kashan style over a period of around one hundred years.

Three of the bowls in this group date to the period when Persian ceramics production reached its absolute zenith during the transformative and experimental period in the workshops at Kashan between c. 1200-1220. The first of these examples, decorated with a long-legged gazelle grazing in a lustrous golden meadow of incised spirals, was painted after an important signed bowl by the potter Muhammad b. Muhammad al-Nishapuri, now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (cat. 2). Of the two other examples from this period, one is characterized by all-over vegetal and stellar ornament that recalls contemporary metalworking forms (cat. 3), while the other, with three plump ducks, a fish, and heavenly orbs above, offers a microcosm of the earthly and heavenly spheres to its viewer (cat. 4). Two further bowls illustrate transitional periods in the Kashan production; the first combining elements of the early ‘Egyptianizing’ wares of the early twelfth century with the new Kashan style of the thirteenth century (cat. 1); and the second made under the aegis of the Mongol Ilkhanate (r. 1256-1335) a generation after the decimation of the region around 1220 (cat. 5).

Each of the objects presented here offers up a world in miniature.

Thanks to their siliceous stonepaste bodies, the ceramics potted at Kashan have solid, yet remarkably thin and light walls and are easily held in two hands. Gazing into the well of these vessels, the viewer is presented with glimmering, lustrous surface ornament imbued with cosmological and astrological significance. The scenes at the centre of Kashan lustre-painted bowls often represent a microcosm of the earthly and heavenly spheres, and are accompanied by poetic and benedictory inscriptions in Persian and Arabic.

Observing and handling these luxurious, finished wares, it can be difficult to imagine the hot, dusty, and oftentimes dangerous environment of the workshop; the constant heating and cooling of various specialised kilns for firing, and the grinding down of metals, minerals, and pigments before they were made into or applied to ceramic bodies. According to the Kashan potter Abu’l-Qasim's treatise of 1301 AD, the sound of molten frit being cooled in water rang out like a clap of roaring thunder that could bring a man to his knees. Nevertheless, after the lustred ceramics emerged from the kiln, they would be polished with wet cloths to reveal their shimmering lustrous glaze, which, in these five remarkable examples, survives much as it must have appeared right out of the kiln.

A lustre-painted bowl with microcosm of the earthly and heavenly spheres, Iran, Kashan, c. 1200-1220

A lustre-painted bowl with gazelle, Attributed to the workshop of Muhammad b. Muhammad al-Nishapuri, Iran, Kashan, c. 1200-1220

‘What have the gazelles to boast of while you have such eyes?’ reads part of the inscription on this cobalt- and lustre-painted bowl.

At its centre, a long-legged gazelle grazes in a lustrous golden meadow of incised spirals. In Persian literary tradition, the gazelle represents an elusive beloved. The canopy of the heavens and the waters of the earth appear above and below. This elegant vessel was painted after an important signed bowl by the potter Muhammad b. Muhammad al-Nishapuri, now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (inv. C.162-1977). It is probably the only known example of a fine Kashan lustre-painted ware made as a direct copy of another bowl by a master in the same workshop.

The Persian poetic inscriptions on the interior comment on the nature of love and loss:

'In the realm of love, grief is no less than happiness / He who is not happy with grief, would not be happy.'

On the outer wall, a Kufic inscription is incised in wide strokes into the lustre glaze, repeating benedictory phrases in Arabic including al-baqa, or ‘long-life’ and al-nasr, or ‘victory’.

A LUSTRE-PAINTED BOWL WITH STELLAR ORNAMENT, IRAN, KASHAN, C. 1200-1220

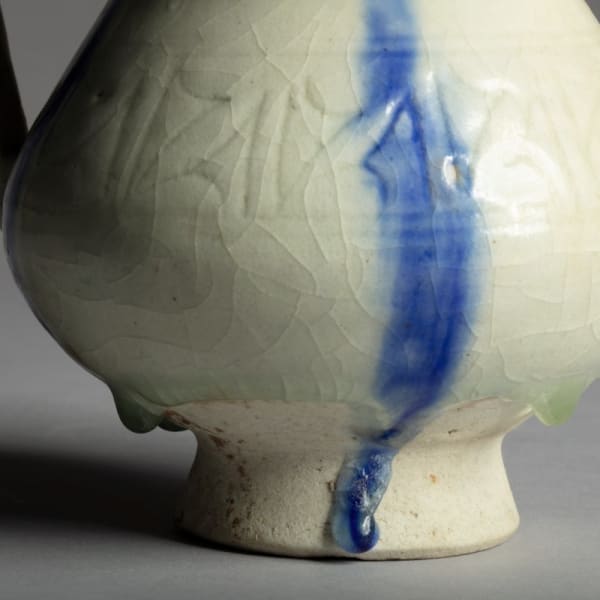

A lustre-painted dish with addorsed birds, Iran, Kashan, c. 1150-1200

This idiosyncratic lustre-painted vessel with addorsed birds has a number of distinctive features that suggest it was made during a transitional period in the development of Kashan styles. The broad, shallow form of the bowl with slightly flattened rim, raised on a short foot, is related to the earliest groups of Kashan lustre-painted wares that relied on Egyptian lustre prototypes. It is a rare and idiosyncratic example of a transitional Kashan lustre vessel that combines design elements of the earliest Kashan wares with the new styles of the early thirteenth century.

A lustre-painted bowl with dragons, Iran, Kashan, c. 1265-1280

Made under the aegis of the Mongol Ilkhanate a generation after the decimation of the region around 1220, the bowl pictured to the left is decorated with confronted dragon heads emerging from a concentric decorative ring filled with a 'scale' motif. It dates to the later period of Kashan lustreware production between c. 1260-1285. This is evidenced in part by the tiny 'ear-muff'-like dots incised through the lustre on the dragons' heads, which are typical of the period. The fearsome form of the dragon probably served an apotropaic function, and also has associations with kingship and divine rule from the Seljuq period (r. in Iran c. 1040-1157) through to the Ilkhanid Period (r. 1256-1335), when this dish was made in the workshops of the Kashan potters.

Many thanks to Melanie Gibson for her insights into this group of ceramics, and to Will Kwiatkowski for attentively reading the inscriptions on a number of these vessels. For long descriptions of each of the objects in the exhibition, and a selection of related literature, please see the PDF catalogue of the exhibition, which you can download at the link above.