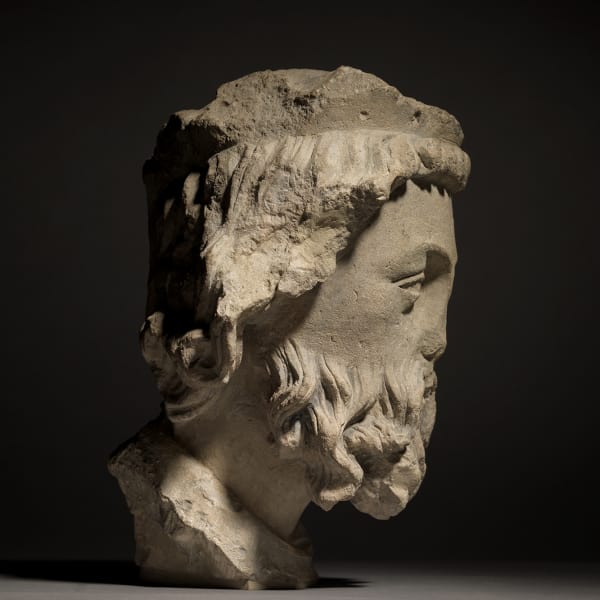

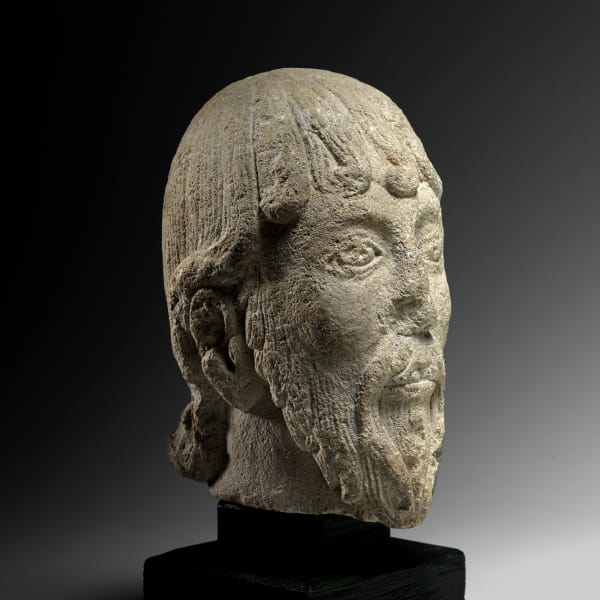

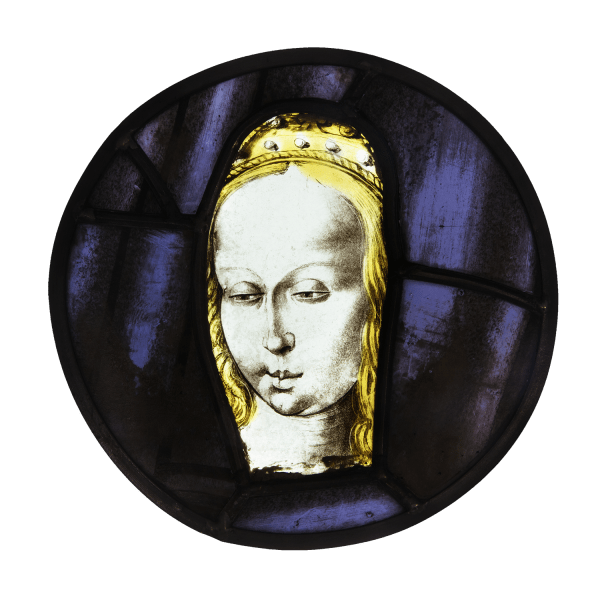

Although severed from the body and their medieval environment, the thirty stone heads in this exhibition provoke a powerful reaction as they warrant us an intimate connection with the past. The individuality of these heads is articulated largely through expression and emotion, which in turn echo those medieval philosophies that saw the head as an indicator of rationality, intelligence and identity. Originating from a variety of contexts and ranging from the 12th to the 15th century, the intrigue and beauty of these sculptures are a testament to the allure that they possess as objects - one of the reasons for their survival in museums and private collections today.

Some of the heads in this exhibition originated from monumental settings. Whether religious or royal, large figures on the exteriors of cathedrals were used to inspire particular political or religious beliefs in people. Statues of kings in such public settings, for example, not only enacted the presence of the king in a symbolic way but were often proxies for his presence in a physical sense – oaths were sworn and judgments were performed in front of these stone portraits. Apart from the heads of kings and saints, other sculptures in this exhibition would have been found in the marginal, shadowy spaces of churches and abbeys, surprising the wondering eyes of the churchgoers with foolish sneers, pained screams and animalistic physiognomies. These fantastic figures would have appeared out of the darkness, from corners and crevices in the cathedral, their grimacing faces demonstrating their absurdity while entertaining their viewers.

The stylistic evolution in the 12th and 13th centuries from abstraction to naturalism was thought to have been practiced in these margins, where sculptors had more freedom to experiment with forms. Idealism gave way to disfigured bodies and dramatic expressions in order to create figures with a heightened presence and the power to move. This commanding presence was revered but also feared - although the sculpted head was created to be looked at, it had the unnerving ability to look back. With the absence of their original context, the stone heads in this exhibition stand as a testament to the damage that has occurred to medieval monuments over the centuries. More importantly, however, they affirm our persistent fascination with the sculpted head as an object.